The ladder of abstractions

The

widely held impression about our human words and thoughts is that they are based

on the real world we are living in. In fact, both words and thoughts are based

on a model of the world, the model one has inside ones head, see the

illustration right and this

comment. So it

could be argued that anyone needs a good understanding of model-making, in order

to have any possibility of understanding the real world.

The

widely held impression about our human words and thoughts is that they are based

on the real world we are living in. In fact, both words and thoughts are based

on a model of the world, the model one has inside ones head, see the

illustration right and this

comment. So it

could be argued that anyone needs a good understanding of model-making, in order

to have any possibility of understanding the real world.

The process of making this model is executed largely unconsciously, being run by the physiology of our sensory systems and the associated parts of the nervous system. The first step in understanding and harnessing it, is the realization that there is a difference between our words and thoughts and the world they stand for: the map is not the territory. Or in other terms: the realization that what we have in our head and what we are talking about are abstractions of the real world.

The way to getting this understanding is greatly helped by the already mentioned fact that everyone has this model of reality inside his head, so unconsciously everyone must know how it works, just like mathematics is in everyone’s head: a baseball player cannot hit a ball without internally calculating trajectories - even though consciously he may be absolutely ignorant about the mathematics of trajectories.

The first explicit and systematic representation of the concepts used when describing the building of these models, abstractions and their relations is originated by Alfred Korzybski in his book Science and Sanity. However, his treatment (using the "structural differential") is a bit sophisticated for an introduction, so here we will adapt the version given by S.I. Hayakawa in Language in Thought and Action, and specifically the way Hayakawa describes the relations between abstractions: the ladder of abstractions.

To illustrate the working of these concepts, we will give a short

introduction to Hayakawa's version, and then analyze what has been said in this

introduction:

Introduction:

Hayakawa’s version starts with a real live animal, Bessie the cow. Bessie lives

at a farm, together with a lot of other cows and animals.

End of introduction.

This simple two-line statement is already full of abstractions. Starting its

analysis with the initial subject, this abstracting begins with the use of the

word “Bessie”. In fact, being a real live animal, Bessie is made up of numerous

components, that are in constant interaction through an even greater number of

processes, leading to ever changing behavior of the entirety. All this diversity

is called "Bessie", and by doing this, we have in fact dropped almost all detail

of all of these components and processes. What we mean by “Bessie” is a limited

number of visible, audible, and behavioral traits that are fairly constant, and

will lead us to remember Bessie during intervals we are not in contact with her.

This is the process of abstraction run by our sensory systems, and the

associated basic processing and interpretation schemes of the brain. This

"Bessie" is an object that occupies the meadow visible in the illustration

above.

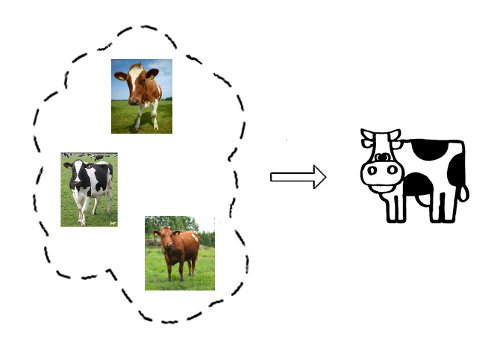

The

second abstraction in the introductory section is the word “cow”. The visible,

audible and behavioral traits that characterize the entity “Bessie”, also apply

for a substantial part to some other entities, while they don’t apply to almost

all others. Since these entities with common characteristics are of some

importance to us humans, we have given this category of entities a name: "cow" -

or in images: the icon-like figure in the right part of the illustration above

and right. "Bessie" is one specific example from this category, say the cow in the

middle of the collection on the left in the picture.

The

second abstraction in the introductory section is the word “cow”. The visible,

audible and behavioral traits that characterize the entity “Bessie”, also apply

for a substantial part to some other entities, while they don’t apply to almost

all others. Since these entities with common characteristics are of some

importance to us humans, we have given this category of entities a name: "cow" -

or in images: the icon-like figure in the right part of the illustration above

and right. "Bessie" is one specific example from this category, say the cow in the

middle of the collection on the left in the picture.

As a member of the category “cow”,

some of Bessie’s characteristics have been lost, that is: all of the

characteristics that distinguish her from other cows (perhaps now you already

can guess the value of the remark “All humans are unique”, to be discussed

further on). With some imagination one can also visualize this category of

"cows" in the first illustration, as one of the things the occupants in the

cubicles on the left side are busy with - the occupants/cubicles being the

separate processes that constitute our higher thinking. The category of "cows"

is handled in one of the cubicles closest to the bridges connecting to the

meadow.

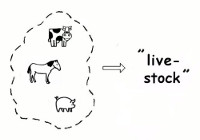

The

next step taken by Hayakawa in his analysis of "the farm" is the taking together

of "cows" with "horses" and "pigs" et cetera into "livestock". Using the same

pictorial scheme as for "cows" gives the illustration on the right. However

note: for "livestock" no really suitable image can be given. Apparently, though

both "cow" and "livestock" are abstractions, "livestock" has a relation to

reality that differs from that of "cow".

The

next step taken by Hayakawa in his analysis of "the farm" is the taking together

of "cows" with "horses" and "pigs" et cetera into "livestock". Using the same

pictorial scheme as for "cows" gives the illustration on the right. However

note: for "livestock" no really suitable image can be given. Apparently, though

both "cow" and "livestock" are abstractions, "livestock" has a relation to

reality that differs from that of "cow".

The

next steps should now be fairly clear - they have been collected by Hayakawa in

his archetypal version of the abstraction ladder, see the illustration alongside

(click on it for an enlarged version). "Bessie" with all her various

characteristics forms the starting point and with each step she loses more of there

characteristics, as she first becomes a "cow", then “livestock”, subsequently part

of the “farm assets” which takes out everything pertaining to her

being alive, “assets” which drops her bonds with the location, the farm, and

finally “wealth”. The last one is also known as “money”, the level that many

people think of as being the most or even only real one, and which in fact is

the most unreal one, as the entire process of abstraction shows. The financial

crisis of 2008 is a potent illustration of this - what seemed to be real, "money

in the bank", vanished without a trace.

The

next steps should now be fairly clear - they have been collected by Hayakawa in

his archetypal version of the abstraction ladder, see the illustration alongside

(click on it for an enlarged version). "Bessie" with all her various

characteristics forms the starting point and with each step she loses more of there

characteristics, as she first becomes a "cow", then “livestock”, subsequently part

of the “farm assets” which takes out everything pertaining to her

being alive, “assets” which drops her bonds with the location, the farm, and

finally “wealth”. The last one is also known as “money”, the level that many

people think of as being the most or even only real one, and which in fact is

the most unreal one, as the entire process of abstraction shows. The financial

crisis of 2008 is a potent illustration of this - what seemed to be real, "money

in the bank", vanished without a trace.

An

essential characteristic of the relations between the different levels of

abstraction is that they are many-to-one relations, as is illustrated in a more

schematic diagram of the abstraction ladder that can be loaded by clicking on

the picture on the right (cows etc. are represented by geometrical symbols).

There are many other examples of “Bessie”, like “Clare” etc., hiding inside the

term “cow” - there are other categories like “horse”, “goat”, etc. hiding inside

“livestock”, and so on.

An

essential characteristic of the relations between the different levels of

abstraction is that they are many-to-one relations, as is illustrated in a more

schematic diagram of the abstraction ladder that can be loaded by clicking on

the picture on the right (cows etc. are represented by geometrical symbols).

There are many other examples of “Bessie”, like “Clare” etc., hiding inside the

term “cow” - there are other categories like “horse”, “goat”, etc. hiding inside

“livestock”, and so on.

So the abstractions can also be seen as a kind of average of a number

of entities at the previous level, just like “gas” describes a specific kind of

average behavior of a lot of atoms. The difference is that in the process of

abstraction, some properties are lost, which is compensated for by that also new

properties may appear. The extra property of a "gas" above that of an "atom",

appears when one cools the gas down: it turns into a liquid, and then a solid.

The physical name for this phenomenon is "phase transition", a concept virtually

unknown to any other science.

The steps on the ladder of abstraction are in fact

phase transitions, one of the reasons why general semantics is such a fruitful

science: it contains a necessary element that the regular social sciences lack.

(Note that there are many more examples of abstraction ladders besides

Hayakawa's "cow"-version. Also note that the "cow"-version has dropped an

important property from Korzybski's original, that describes the process of

observation itself and has its highest abstractions ("particles", "fields")

pointing back to the lowest level physical world, making it a circular process,

just

like science itself)

The important thing about the knowledge of the ladder of abstractions, now

almost obvious, is that what may be true as a rule between things at the

same level of abstraction, almost certainly isn’t true when one changes the

level of the entities in the rule. For example, going back to the farm one might

formulate the rule that putting cow with cow (if the latter is a male specimen)

leads to more cows. However, applying the rule to livestock or farm animals,

will in general not lead to more farm animals, and in some unfortunate cases to

less.

In the previous example, both elements of the rule were replaced by elements at

the same abstraction level, and in this case one might see instances where the

new rule works. In case one changes one of the elements in the rule to another

abstraction level, while the others remain the same or go to a different level,

the chances of the rule remaining valid get very slim indeed.

How basic these observations may seem, they are violated in almost every

discussion on any political or cultural or philosophical subject. Even in plain

practical live, people are for the most part completely unaware of these

processes of abstraction. “What is red?” – “Red is a color” – “What is a

color?”, may soon turn into an angry exchange of words that leads to nothing,

because both parties are unaware of what they are doing. You can imagine what

happens when one has this kind of discussion when it involves terms like

“Chinese” or having similar racial content, “freedom” or other high level terms

of politics, etc. Observations made by Hayakawa, and treated in detail in

his book.

This website (at present almost entirely in a

Dutch version) is

also on political, cultural, and philosophical subjects. Here, an attempt is

made to discuss these sensitive issues while being aware and observing the rules

of the ladder of abstraction. A first small step was the use of the link symbols

introduced on the home page, by having the direction of the arrows coincide more

or less with the directions of the ladder of abstractions.

One of the results of applying the ladder of abstractions is that one can

eliminate a lot of nonsense from the discussions on political, cultural, and

philosophical matters. Remember the earlier mentioned statement “All humans are

unique”. The knowledge of the abstraction ladder learns that this is an empty

statement, until one answers the question “Unique to what (at what level of

abstraction)?”. The statement has the same value as a commercial statement like:

“Our lamps gives off 30 % more light”, which is senseless because it isn’t

mentioned what value the 30 % refers to. There may be some level at which humans

are unique, but this is at the same level as the statement “All snowflakes are

unique” is true. The latter is the result of serious research, and the

variations are as least as beautiful as those in humans, see

here

![]() .

.

Uniqueness is a concept that applies to everything at the proper level, so as a distinguishing

property of humanity it has no value at all. And the other way around: what applies to snowflakes: “In

most practical circumstances snowflakes can be considered identical”, equally

applies to all of these statements, i.e. including “All humans are unique”.

Armed with this knowledge, one can formulate rules on human behavior in the same

manner as physicists do this with gases, thereby considering humans identical in

a lot of practical circumstances. An idea worked upon in several sciencefiction

books, most notably Asimov's

Foundation trilogy.

This description of the ladder of abstractions is no more then a quick

introduction, the given references contain more detail. Some steps are also

worked out a little further here, starting with the elementary first step:

The Abstraction of Observation

![]() .

.

The concept of the ladder of abstraction is in the original and much larger

Dutch section of this

website applied on higher level: the distinct scientific disciplines - an

English introduction has been given

here

![]() .

This is very much in the vain of the original intention of Korzybski, whose

intention, as stated in the introduction of Science and Sanity, was to

improve the working of the human scientific disciplines to the level of the

natural ones. This approach starts here

.

This is very much in the vain of the original intention of Korzybski, whose

intention, as stated in the introduction of Science and Sanity, was to

improve the working of the human scientific disciplines to the level of the

natural ones. This approach starts here

![]() .

.

Go to General semantics list

here

![]() , all

articles here

, all

articles here

![]() , site home here

, site home here

![]() .

.