| |

How Animals Do Business

Humans and other animals share a heritage of economic tendencies-including

cooperation, repayment of favors and resentment at being shortchanged

Just as my office would not stay empty for long were I to move out, nature's

real estate changes hands all the time. Potential homes range from holes

drilled by woodpeckers to empty shells on the beach. A typical example of

what economists call a "vacancy chain" is the housing market among hermit

crabs. To protect its soft abdomen, each crab carries its house around,

usually an abandoned gastropod shell. The problem is that the crab grows,

whereas its house does not. Hermit crabs are always on the lookout for new

accommodations. The moment they upgrade to a roomier shell, other crabs line

up for the vacated one.

One can easily see supply and demand at work here, but because it plays

itself out on a rather impersonal level, few would view the crab version as

related to human economic transactions. The crab interactions would be more

interesting if the animals struck deals along the lines of "you can have my

house if I can have that dead fish." Hermit crabs are not deal makers,

though, and in fact have no qualms about evicting homeowners by force.

Other, more social animals do negotiate, however, and their approach to the

exchange of resources and services helps us understand how and why human

economic behavior may have evolved.

|

Capuchin monkeys share food just as

chimpanzees and humans do. Rare among other primates, this practice may have

evolved along with cooperative hunting, a strategy used by all three

species. Without joint payoffs, there would be no joint hunting. Here a

juvenile capuchin begs for a share by cupping his hand next to the food an

adult male is eating. |

The New Economics

Classical economics views people as profit maximizers driven by pure

selfishness. As 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes put it, "Every

man is presumed to seek what is good for himselfe naturally, and what is just,

only for Peaces sake, and accidentally." In this still prevailing view,

sociality is but an afterthought, a "social contract" that our ancestors entered

into because of its benefits, not because they were attracted to one another.

For the biologist, this imaginary history falls as wide off the mark as can be

We descend from a long line of group living primates, meaning that we are

naturally equipped with a strong desire to fit in and find partners to live and

work with. This evolutionary explanation for why we interact as we do is gaining

inf1uence with the advent of a new school, known as behavioral economics, that

focuses on actual human behavior rather than on the abstract forces of the

marketplace as a guide for understanding economic decision making. In 2002 the

school was recognized by a shared Nobel Prize for two of its founders: Daniel

Kahneman and Vernon L. Smith.

Animal behavioral economics is a fledgling field that lends

support to the new theories by showing that basic human economic tendencies and

preoccupations-such as reciprocity, the division of rewards, and cooperation-are

not limited to our species. They probably evolved in other animals for the same

reasons they evolved in us-to help individuals take optimal advantage of one

another without undermining the shared interests that support group life.

Take a recent incident during my research at the Yerkes

National Primate Research Center in Atlanta. We had taught capuchin monkeys to

reach a cup of food on a tray by pulling on a bar attached to the tray. By

making the tray too heavy for a single individual, we gave the monkeys a reason

to work together.

On one occasion, the pulling was to be done by two females,

Bias and Sammy. Sitting in adjoining cages, they successfully brought a tray

bearing two cups of food within reach. Sammy, however, was in such a hurry to

collect her reward that she released the bar and grabbed her cup before Bias had

a chance to get hers. The tray bounced back, out of Bias's reach. While Sammy

munched away, Bias threw a tantrum. She screamed her lungs out for half a minute

until Sammy approached her pull bar again. She then helped Bias bring in the

tray a second time. Sammy did not do so for her own benefit, because by now the

cup accessible to her was empty.

Sammy's corrective behavior appeared to be a response to

Bias's protest against the loss of an anticipated reward. Such action comes much

closer to human economic transactions than that of the hermit crabs, because it

shows cooperation, communication and the fulfillment of an expectation, perhaps

even a sense of obligation. Sammy seemed sensitive to the quid pro quo of the

situation. This sensitivity is not surprising given that the group life of

capuchin monkeys revolves around the same mixture of cooperation and competition

that marks our own societies.

|

|

| |

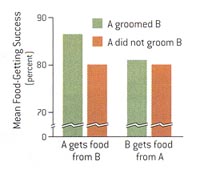

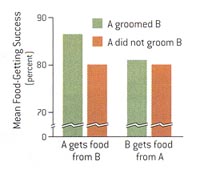

CHIMPANZEES share food - these branches with leaves, for

example-in return for favors such as grooming. This reciprocity was

demonstrated experimentally by recording groomings on the mornings of

days when food-sharing tests were scheduled. As the graph shows, chimp

A's success in obtaining food from chimp B increased after A had groomed

B, but B's success in obtaining food from A was unaffected by A's

grooming. Thus, it is specifically the groomer who benefits, meaning

that the rule is one of exchange of food for grooming. |

|

|

The Evolution of Reciprocity

Animals and people occasionally help one another without any obvious benefits

for the helper. How could such behavior have evolved? If the aid is directed at

a family member, the question is relatively easy to answer. "Blood is thicker

than water," we say, and biologists recognize genetic advantages to such

assistance: if your kin survive, the odds of your genes making their way into

the next generation increase. But cooperation among unrelated individuals

suggests no immediate genetic advantages. Petr Kropotkin, a Russian prince,

offered an early explanation in his book Mutual Aid, published in 1902.

If helping is communal, he reasoned, all parties stand to gain - everyone's

chances for survival go up. We had to wait until 1971, however, for Robert L.

Trivers, then at Harvard University, to phrase the issue in modern evolutionary

terms with his theory of reciprocal altruism.

Trivers contended that making a sacrifice for another pays

off if the other later returns the favor. Reciprocity boils down to "I'll

scratch your back, if you scratch mine." Do animals show such tit for tat?

Monkeys and apes form coalitions; two or more individuals, for example, gang up

on a third. And researchers have found a positive correlation between how of ten

A supports B and how of ten B supports A. But does this mean that animals

actually keep track of given and received favors? They may just divide the world

into "buddies," whom they prefer, and "nonbuddies," whom they care little about.

If such feelings are mutual, relationships will be either mutually helpful or

mutually unhelpful. Such symmetries can account for the reciprocity reported for

fish, vampire bats (which regurgitate blood to their buddies), dolphins and many

monkeys.

Just because these animals may not keep track of favors does

not mean they lack reciprocity. The issue rather is how a favor done for another

finds its way back to the original altruist. What exactly is the reciprocity

mechanism? Mental record keeping is just one way of getting reciprocity to work,

and whether animals do this remains to be tested. Thus far chimpanzees are the

only exception. In the wild, they hunt in teams to capture colobus monkeys. One

hunter usually captures the prey, after which he tears it apart and shares it.

Not everyone gets a piece, though, and even the highest-ranking male, if he did

not take pan in the hunt, may beg in vain. This by itself suggests reciprocity:

hunters seem to enjoy priority during the division of spoils.

To try to find the mechanisms at work here, we exploited the

tendency of these apes to share - which they also show in captivity - by handing

one of the chimpanzees in our colony a watermelon or some branches with leaves.

The owner would be at the center of a sharing cluster, soon to be followed by

secondary clusters around individuals who had managed to get a major share,

until all the food had trickled down to everyone. Claiming another's food by

force is almost unheard of among chimpanzees-a phenomenon known as "respect of

possession." Beggars hold out their hand, palm upward, much like human beggars

in the street. They whimper and whine, but aggressive confrontations are rare.

If these do occur, the possessor almost always initiates them to make someone

leave the circle. She whacks the offenders over the head with a sizable branch

or barks at them in a shrill voice until they leave her alone. Whatever their

rank, possessors control the food flow.

We analyzed nearly 7,000 of these approaches, comparing the

possessor's tolerance of specific beggars with previously received services. We

had detailed records of grooming on the mornings of days with planned food

tests. If the top male, Socko, had groomed May, for example, his chances of

obtaining a few branches from her in the afternoon were much improved. This

relation between past and present behavior proved genera!. Symmetrical

connections could not explain this outcome, as the pattern varied from day to

day. Ours was the first anima I study to demonstrate a contingency between

favors given and received. Moreover, these food-for-grooming deals were

partner-specific that is, May's tolerance benefited Socko, the one who had

groomed her, but no one else.

This reciprocity mechanism requires memory of previous events

as well as the coloring of memory such that it induces friendly behavior. In our

own species, this coloring process is known as "gratitude," and there is no

reason to call it something else in chimpanzees. Whether apes also feel

obligations remains unclear, but it is interesting that the tendency to return

favors is not the same for all relationships. Between individuals who associate

and groom a great deal, a single grooming session carries little weight. All

kinds of daily exchanges occur between them, probably without their keeping

track. They seem instead to follow the buddy system discussed before. Only in

the more distant relationships does grooming stand out as specifically deserving

reward. Because Socko and May are not close friends, Socko's grooming was duly

noticed.

A similar difference is apparent in human behavior, where we

are more inclined to keep track of give-and-take with strangers and colleagues

than with our friends and family. In fact, scorekeeping in close relationships,

such as between spouses, is a sure sign of distrust.

|

What Makes Reciprocity Tick |

| Humans and other animals exchange benefits in

several ways, known technically as reciprocity mechanisms. No matter what

the mechanism, the common thread is that benefits find their way back to the

original giver. |

| Reciprocity mechanism |

|

Key features |

Symmetry-based

"We're buddies" |

|

Mutual affection between two parties prompts

similar behavior in both directions without need to keep track of daily

give-and-take, so long as the overall relationship remains satisfactory.

Possibly the most common mechanism of reciprocity in nature, this kind is

typical of humans and chimpanzees in close relationships.

Example: Chimpanzee friends associate, groom together and support each

other in fights. |

| |

|

|

Attitudinal

"If you're nice, I'll be nice" |

|

Parties mirror one another's attitudes,

exchanging favors on the spot. Instant attitudinal reciprocity occurs among

monkeys, and people of ten rely on it with strangers.

Example: Capuchins share food with those who help them pull a

treat-laden tray. |

| |

|

|

Calculated

"What have you done for me lately?" |

|

Individuals keep track of the benefits they

exchange with particular partners, which helps them decide to whom to return

favors. This mechanism is typical of chimpanzees and common among people in

distant and professional relationships.

Example: Chimpanzees can expect food in the afternoon from those they

groomed in the morning. |

|

Biological Markets

Because reciprocity requires partners, partner choice ranks as a central issue

in behavioral economics. The hand-me-down housing of hermit crabs is exceedingly

simple compared with the interactions among primates, which involve multiple

partners exchanging multiple currencies, such as grooming, sex, support in

fights, food, babysitting and so on. This "marketplace of services," as I dubbed

it in Chimpanzee Politics, means that each individual needs to be on good

terms with higher-ups, to foster grooming partnerships and-if ambitious-to

strike deals with like-minded others. Chimpanzee males form coalitions to

challenge the reigning ruler, a process fraught with risk. After an overthrow,

the new ruler needs to keep his supporters contented: an alpha male who tries to

monopolize the privileges of power, such as access to females, is unlikely to

keep his position for long. And chimps do this without having read Niccola

Machiavelli.

With each individual shopping for the best partners and

selling its own services, the framework for reciprocity becomes one of supply

and demand, which is precisely what Ronald Noë and Peter Hammerstein, then at

the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology in Seewiesen, Germany, had in

mind with their biological market theory. This theory, which applies whenever

trading partners can choose with whom to deal, postulates that the value of

commodities and partners varies with their availability. Two studies of market

forces elaborate this point: one concerns the baby market among baboons, the

other the job performance of small fish called cleaner wrasses.

Like all primate females, female baboons are irresistibly

attracted to infants-not only their own but also those of others. They give

friendly grunts and try to touch them. Mothers are highly protective, however,

and reluctant to let anyone handle their precious newborns. To get close,

interested females groom the mother while peeking over her shoulder or

underneath her arm at the baby. After a relaxing grooming session, a mother may

give in to the groomer's desire for a closer look. The other thus buys infant

time. Market theory predicts that the value of babies should go up if there are

fewer around. In a study of wild chacma baboons in South Africa, Louise Barrett

of the University of Liverpool and Peter Henzi of the University of Central

Lancashire, both in England, found that, indeed, mothers of rare infants were

able to extract a higher price (longer grooming) than mot hers in a troop full

of babies.

|

BABOON FEMALES pay a price in grooming to get a peek at a

new infant; the fewer the infants, the longer the grooming required. The

value of commodities - baby baboons in this case - increases as their

availability decreases. |

Cleaner wrasses (Labroides dimidiatus) are small

marine fish that feed on the external parasites of larger fish. Each cleaner

owns a "station" on a reef where clientele come to spread their pectoral fins

and adopt postures that offer the cleaner a chance to do its job. The exchange

exemplifies a perfect mutualism.

The cleaner nibbles the parasites off the client's body

surface, gills and even the inside of its mouth. Sometimes the cleaner is so

busy that clients have to wait in line. Client fish come in two varieties:

residents and roamers. Residents belong to species with small territories; they

have no choice but to go to their local cleaner. Roamers, on the other hand,

either hold large territories or travel widely, which means that they have

several cleaning stations to choose from.

They want short waiting times, excellent service and no cheating. Cheating

occurs when a cleaner fish takes a bite out of its client, feeding on healthy

mucus. This makes clients jolt and swim away.

Research on cleaner wrasses by Redouan Bshary of the Max

Planck institute in Seewiesen consists mainly of observations on the reef but

also includes ingenious experiments in the laboratory. His papers read much like

a manual for good business practice. Roamers are more likely to change stations

if a cleaner has ignored them for too long or cheated them. Cleaners seem to

know this and treat roamers better than they do residents. If a roamer and a

resident arrive at the same time, the cleaner almost always services the roamer

first. Residents have nowhere else to go, and so they can be kept waiting. The

only category of fish that cleaners never cheat are predators, who possess a

radical counterstrategy, which is to swallow the cleaner. With predators,

cleaner fish wisely adopt, in Bshary's words, an "unconditionally cooperative

strategy."

|

|

| |

CLEANER FISH nibbles parasites in the open mouth of a

large client fish. Roaming client fish rarely return to the station of a

cleaner fish after they have been kept waiting (left graph) or cheated

(right graph), meaning that the cleaner took a bite out of the client's

healthy tissue. Cleaner fish therefore tend to treat roaming clients

better than residents, who have no choice of cleaning stations. |

|

|

Biological market theory

offers an elegant solution to the problem of freeloaders, which has occupied

biologists for a long time because reciprocity systems are obviously vulnerable

to those who take rather than give. Theorists often assume that offenders must

be punished, although this has yet to be demonstrated for animals. Instead

cheaters can be taken care of in a much simpler way. If there is a choice of

partners, animals can simply abandon unsatisfactory relationships and replace

them with those offering more benefits. Market mechanisms are all that is needed

to sideline profiteers. In our own societies, too, we neither like nor trust

those who take more than they give, and we tend to stay away from them.

Fair Is Fair

To reap the benefits of cooperation, an individual must monitor its efforts

relative to others and compare its rewards with the effort put in. To explore

whether animals actually carry out such monitoring, we turned again to our

capuchin monkeys, testing them in a miniature labor market inspired by field

observations of capuchins attacking giant squirrels. Squirrel hunting is a group

effort, but one in which all rewards end up in the hands of a single individual:

the captor. If captors were to keep the prey solely for themselves, one can

imagine that others would lose interest in joining them in the future. Capuchins

share meat for the same reason chimpanzees (and people) do: there can be no

joint hunting without joint payoffs.

We mimicked this situation in the laboratory by making

certain that only one monkey (whom we called the winner) of a tray-pulling pair

received a cup with apple pieces. Its partner (the laborer) had no food in its

cup, which was obvious from the outset because the cups were transparent. Hence,

the laborer pulled for the winner's benefit. The monkeys sat side by side,

separated by mesh. From previous tests we knew that food possessors might bring

food to the partition and permit their neighbor to reach for it through the

mesh. On rare occasions, they push pieces to the other.

We contrasted collective pulls with solo pulls. In one

condition, both animals had a pull bar and the tray was heavy; in the other, the

partner lacked a bar and the winner hand led a lighter tray on its own. We

counted more acts of food sharing after collective than solo pulls: winners were

in effect compensating their partners for the assistance they had received. We

also confirmed that sharing affects future cooperation. Because a pair's success

rate would drop if the winner failed to share, payment of the laborer was a

smart strategy.

|

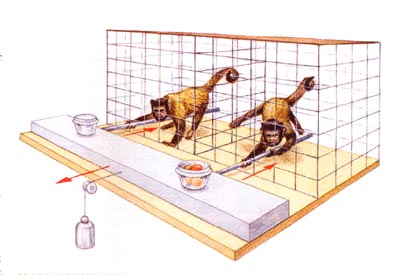

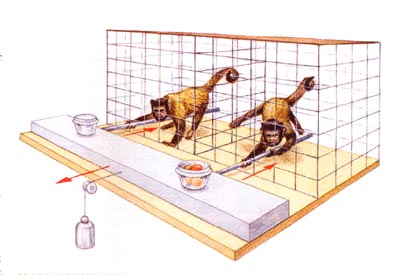

| |

TRAY-PULLING EXPERIMENT demonstrates that capuchin

monkeys are more likely to share food with cooperative partners than

with those who are not helpful. The test chamber houses two capuchins,

separated by mesh. To reach their treat cups, they must use a bar to

pull a counterweighted tray; the tray is too heavy for one monkey to

handle alone. The "laborer" (on left), whose transparent cup is

obviously empty, works for the "winner," who has food in its cup. The

winner generally shares food with the laborer through the mesh. Failing

to do so will cause the laborer to lose interest in the task. |

|

|

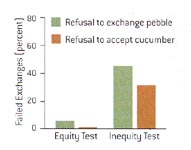

Sarah F. Brosnan, one of my colleagues at Yerkes, went

further in exploring reactions to the way rewards are divided. She would offer a

capuchin monkey a small pebble, then hold up a slice of cucumber as enticement

for returning the pebble. The monkeys quickly grasped the principle of exchange.

Placed side by side, two monkeys would gladly exchange pebbles for cucumber with

the researcher. If one of them got grapes, however, whereas the other stayed on

cucumber, things took an unexpected turn. Grapes are much preferred. Monkeys who

had been perfectly willing to work for cucumber suddenly went on strike. Not

only did they perform reluctantly seeing that the other was getting a better

deal, but they became agitated, hurling the pebbles out of the test chamber and

sometimes even the cucumber slices. A food normally never refused had become

less than desirable.

|

|

| |

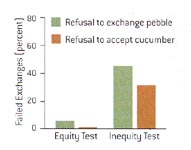

CAPUCHIN MONKEYS have definite preferences when it comes

to food. They will, for example, choose fruit over vegetables, such as

the celery this capuchin is thoughtfully consuming. Trained to exchange

a pebble for a slice of cucumber, they happily did so as long as the

monkey in the adjoining test chamber also received cucumber (Equity Test

on graph). But when the monkey next door was given a grape while they

continued to receive cucumber (Inequity Test), they balked at "unfair

pay". They either refused to accept the cucumber, sometimes even

throwing it out of the cage, or refused to return the pebble. |

|

|

To reject unequal pay-which people do as well-goes against

the assumptions of traditional economics. If maximizing benefits we re all that

mattered, one should take what one can get and never let resentment or envy

interfere. Behavioral economists, on the other hand, assume evolution has led to

emotions that preserve the spirit of cooperation and that such emotions

powerfully influence behavior. In the short run, caring about what others get

may seem irrational, but in the long run it keeps one from being taken advantage

of. Discouraging exploitation is critical for continued cooperation.

It is a lot of trouble, though, to always keep a watchful eye

on the flow of benefits and favors. This is why humans protect themselves

against freeloading and exploitation by forming buddy relationships with

partners - such as spouses and good friends - who have withstood the test of

time. Once we have determined whom to trust, we relax the rules. Only with more

distant partners do we keep mental records and react strongly to imbalances,

calling them "unfair."

We found indications for the same effect of social distance

in chimpanzees.

Straight tit for tat, as we have seen, is rare among friends who routinely do

favors for one another. These relationships also seem relatively immune to

inequity. Brosnan conducted her exchange task using grapes and cucumbers with

chimpanzees as well as capuchins. The strongest reaction among chimpanzees

concerned those who had known one another for a relatively short time, whereas

the members of a colony that had lived together for more than 30 years hardly

reacted at all. Possibly, the greater their familiarity, the longer the time

frame over which chimpanzees evaluate their relationships. Only distant

relations are sensitive to day-to-day fluctuations.

All economic agents, whether human or animal, need to come to

grips with the freeloader problem and the way yields are divided after joint

efforts. They do so by sharing most with those who help them most and by

displaying strong emotional reactions to violated expectations. A truly

evolutionary discipline of economics recognizes this shared psychology and

considers the possibility that we embrace the golden rule not accidentally, as

Hobbes thought, but as part of our background as cooperative primates.

Editorial:

How Humans Do Business

The emotions that Frans de Waal describes in the economic exchanges of social

animals have parallels in our own transactions. Such similarities suggest that

human economic interactions are controlled at least in part by ancient

tendencies and emotions. Indeed, the animal work supports a burgeoning school of

research known as behavioral economics. This new discipline is challenging and

modifying the "standard model" of economic research, which maintains that humans

base economic decisions on rational thought processes. For example, people

reject offers that strike them as unfair, whereas classical economics predicts

that people take anything they can get. In 2002 the Nobel Prize in Economics

went to two pioneers of the field: Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist at Princeton

University, and Vernon L. Smith, an economist at George Mason University.

Kahneman, with his colleague Amos Tversky, who died in 1996

and thus was not eligible for the prize, analyzed how humans make decisions when

confronted by uncertainty and risk. Classical economists had thought of human

decisions in terms of expected utility-the sum of the gains people think they

will get from some future event multiplied by its probability of occurring. But

Kahneman and Tversky demonstrated that people are much more frightened of losses

than they are encouraged by potential gains and that people follow the herd. The

bursting of the stock-market bubble in 2000 provides a potent example: the

desire to stay with the herd may have led people to shell out far more for

shares than any purely rational investor would have paid.

Smith's work demonstrated that laboratory experiments would

function in economics, which had traditionally been considered a nonexperimental

science that relied solely on observation. Among his findings in the lab:

emotional decisions are not necessarily unwise. - The Editors

FRANS B. M. DE WAAL is C. H. Candler Professor of Primate Behavior at Emory

University and director of the Living Links Center at the university's

Yerkes National Primate Research Center. De Waal specializes in the social

behavior and cognition of monkeys, chimpanzees and bonobos, especially

cooperation, conflict resolution and culture. His books include

Chimpanzee Politics,

Peacemaking among Primates, The Ape and the Sushi Master and the

forthcoming Our Inner Ape.

MORE TO EXPLORE

The Chimpanzee's Service Economy: Food for Grooming. Frans B. M. de Waal

in

Evolution and Human Behaviar, Vol. 18, No. 6, pages 375-386; November

1997.

Payment for Labour in Monkeys. Frans B. M. de Waal and Michelle L. Berger

in Nature, Vol. 404, page 563; April 6, 2000.

Choosy Reef Fish Select Cleaner Fish That Provide High-Ouality Service.

R. Bshary and O. Schäffer in

Animal Behaviour, Vol. 63, No. 3, pages 557-564; March 2002.

Infants as a Commodity in a Baboon Market. S. P. Henzi and L. Barrett in

Animal Behaviour, Vol. 63, No. 5, pages 915-921; 2002.

Monkeys Reject Unequal Pay. Sarah F. Brosnan and Frans B. M. de Waal in

Nature, Vol. 425, pages 297-299; September 18, 2003.

Living Links Center site:

www.emory.edu/LIVING_LINKS/

Classic cooperation experiment with chimpanzees: www.emory.edu/LiVING_LINKS/

crawfordvideo.html

|

(Scientific American, April 2005, by Frans B. M. de Waal):

(Scientific American, April 2005, by Frans B. M. de Waal):