The ladder of abstractions

This article has been updated as of 08-10-2016 - here is the previous version Note: the arrows are the links. The "ladder of

abstractions" or "abstraction ladder" is a concept taken from the field of

general semantics

The "ladder of

abstractions" or "abstraction ladder" is a concept taken from the field of

general semantics

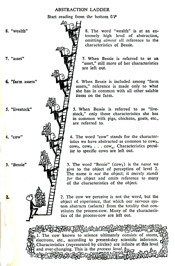

The process of making this model is executed mostly unconsciously, by our sensory organs and the large number of neurological structures attached to them. The evolutional drive behind developing this system is that it is advantageous to be able to distinguish between preditory life forms and friendly or indifferent ones, i.e. to be able to collect these into separate and distinguishable groups. These groups aren't objects existing in the real world, thus creating a distinction between objects in the model that are and those that aren't part of the real world, the "abstractions" - the most obvious feature of the first illustration.

This capacity is present in many species, amongst whom certainly those that are able to warn each other for danger. It is developed the farthest in humankind, in a form known as "speech". Which has led to more kinds of abstractions, known as "higher abstractions".

The abstraction ladder is an attempt to a systematic approach to the relations between the kinds of groups of all sorts, including the "abstractions", when these are expressed in words. This is the analagon in speech or language of the neurological processes taking place in the brain when distinguishing between species. This description starts by analyzing the different kinds of words.

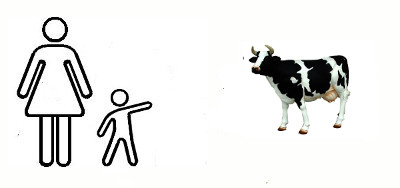

The first kind of word and also a prime candidate to be the

origin of the development of speech are here called "object words" - words

that denotes things that you can point to in the real world. They are an

necessity in order to be able to make a connection between a specific utterance of

sounds coming out of your mouth and the objects in de the real world. Even

"modern" kids start to learn language this way, for the example in the

illustration: Mama: "There is Bessie!".

The first kind of word and also a prime candidate to be the

origin of the development of speech are here called "object words" - words

that denotes things that you can point to in the real world. They are an

necessity in order to be able to make a connection between a specific utterance of

sounds coming out of your mouth and the objects in de the real world. Even

"modern" kids start to learn language this way, for the example in the

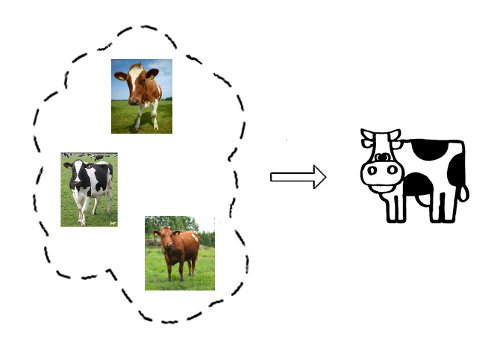

illustration: Mama: "There is Bessie!".  The second kind of words are those of the

natural collections of these objects, in this case: all of the objects that

look like "Bessie": "Clare", "Mathilda" etc., where "Clare" and "Mathilda"

are the "object words" connected to two other "cows" that occupy the meadow

of the farm, where "cows" is the word for the collection of traits that

these three (and probably more) have in common. Whereby also a lot of the

individual traits of Bessie etc. have been lost. The fact that a lot of traits are lost while retaining certain others, is denoted by the

other word for this collection: "abstraction".

The second kind of words are those of the

natural collections of these objects, in this case: all of the objects that

look like "Bessie": "Clare", "Mathilda" etc., where "Clare" and "Mathilda"

are the "object words" connected to two other "cows" that occupy the meadow

of the farm, where "cows" is the word for the collection of traits that

these three (and probably more) have in common. Whereby also a lot of the

individual traits of Bessie etc. have been lost. The fact that a lot of traits are lost while retaining certain others, is denoted by the

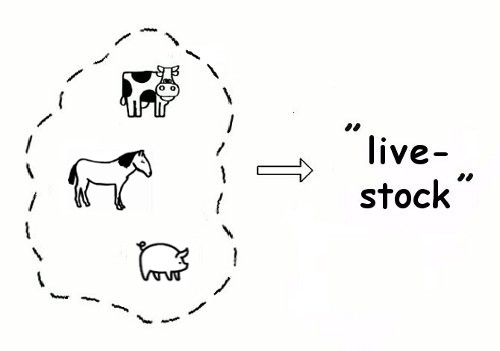

other word for this collection: "abstraction".  Tom's farm is also the residence of other objects besides "cows".

"Horses" and "pigs" are quite different from "cows", but to farmer Tom they

also have similarities: they all require feed, they all produce manure,

etc. These common traits are abbreviated into the word "livestock", which

can also be seen as a "collection of collections". Note there is in general no

natural way to associate a symbol with these "collections of collections"

Tom's farm is also the residence of other objects besides "cows".

"Horses" and "pigs" are quite different from "cows", but to farmer Tom they

also have similarities: they all require feed, they all produce manure,

etc. These common traits are abbreviated into the word "livestock", which

can also be seen as a "collection of collections". Note there is in general no

natural way to associate a symbol with these "collections of collections"

As part of the collection of "livestock", Bessie loses even more of her specific traits: giving milk (at least: as a mass-producer), and also for example her color: cows are frequently black-and-white, horses are brown and pigs are pink. So note: one cannot have "the color of livestock".

It should be clear that this last addition to the kinds of words opens the

floodgates. For example: one can combine farmer Tom's "live stock" with all

of the machinery he needs for his work into "farm assets". Possible further

steps are "property", and "wealth" or "capital". Those are the steps used by

the originator of this version of "the ladder of abstractions", S.I.

Hayakawa

It should be clear that this last addition to the kinds of words opens the

floodgates. For example: one can combine farmer Tom's "live stock" with all

of the machinery he needs for his work into "farm assets". Possible further

steps are "property", and "wealth" or "capital". Those are the steps used by

the originator of this version of "the ladder of abstractions", S.I.

Hayakawa

But other classifications are equally possible: farmer Tom's property is part of the agricultural assets of the village, the village is an element of the region, the regions make up the country, etc. So not only are the floodgates opened as far as the depth of the abstractions is concerned, but this also applies to their width. In fact, the possibilities of making abstractions never end - the universe is probably big enough for all of them. But this limitation never comes into sight, because where it is possible to have any number of them, most of them have little or no practical use: one can take cows together with peeling knives, but it hardly seems to make any sense (of course: creative types will have a go after such a statement).

This is the model as developed in the field of general semantics. It is now going to be extended with some new features. First of all the abstraction ladder is generalized, and this generalization leads the way to what was also an ultimate goal of Korzybski: the connection with neurology and psychology.

The

pivotal point in the abstraction ladder is that every step on it does two

things: like the one taken from cows to farm animals, it enlarges the scope

of the objects, and at the same time it takes away specific traits of the

objects. To further illustrate this point, an interactive model has been

made using the simplest objects: triangles, squares etc. - click on the

illustration (right) to start this. Which immediately introduces an aspect

that is not easy to incorporate into natural models: even the first kind of

collections are not an obvious choice. And it also illustrates that this

choice matters: taking color as an ordering criterium, ends the process

immediately. So besides that the making collections or abstractions is a

crucial step, the choice of which kind of collections i.e. the choice of

criteria is equally vital. It should be clear that the higher the

abstractions that can be build, the more able they will be to see higher

patterns in the environment and thereby to predict future events, leading to

better survivability. And since nature is variable, these criteria shoud not

be build in, but to be learned.

The

pivotal point in the abstraction ladder is that every step on it does two

things: like the one taken from cows to farm animals, it enlarges the scope

of the objects, and at the same time it takes away specific traits of the

objects. To further illustrate this point, an interactive model has been

made using the simplest objects: triangles, squares etc. - click on the

illustration (right) to start this. Which immediately introduces an aspect

that is not easy to incorporate into natural models: even the first kind of

collections are not an obvious choice. And it also illustrates that this

choice matters: taking color as an ordering criterium, ends the process

immediately. So besides that the making collections or abstractions is a

crucial step, the choice of which kind of collections i.e. the choice of

criteria is equally vital. It should be clear that the higher the

abstractions that can be build, the more able they will be to see higher

patterns in the environment and thereby to predict future events, leading to

better survivability. And since nature is variable, these criteria shoud not

be build in, but to be learned. So having concluded that at least in humankind the process of building

abstractions is something that has to be learned, at least in some respects,

the next question is: where and how? The first question has already been

answered, in recent research

So having concluded that at least in humankind the process of building

abstractions is something that has to be learned, at least in some respects,

the next question is: where and how? The first question has already been

answered, in recent research

So where the hippocampus is the location where the impressions of the sensory organs are analyzed into concepts, using them for "recognition" (note: to re-cognize: "to make sense of again"), this probably also is the place where the abstractions are learned. Thus the place where, say by starting with "trial and error", effective abstractions are enhanced and made permanent and ineffective ones are discouraged and discarded. And anybody knowing anything about neurology knows how things are stimulated in the brain: by the use of dopamine.

Thereby almost coming to the essence of these new additions to the

ladder of abstractions: any process in the brain that involves dopamine is

subject to the potential of addiction. In this case: the higher a concept,

the more likely it is to lead to a hit, the more it is stimulated by the

freeing of dopamine, the more prominent the concept becomes in the

hippocampus, the more likely it leads to a hit, etc. Together: higher

concepts are potentially addictive. A large part of the book by Hayakawa is

devoted to describing and correcting errors made both verbally and in

the actual world that are the consequence of the erroneous use op abstractions, in

most cases due to the addictiveness of higher abstractions. Errors having

descriptive and colorful names like "dead level abstracting"

Thereby almost coming to the essence of these new additions to the

ladder of abstractions: any process in the brain that involves dopamine is

subject to the potential of addiction. In this case: the higher a concept,

the more likely it is to lead to a hit, the more it is stimulated by the

freeing of dopamine, the more prominent the concept becomes in the

hippocampus, the more likely it leads to a hit, etc. Together: higher

concepts are potentially addictive. A large part of the book by Hayakawa is

devoted to describing and correcting errors made both verbally and in

the actual world that are the consequence of the erroneous use op abstractions, in

most cases due to the addictiveness of higher abstractions. Errors having

descriptive and colorful names like "dead level abstracting"

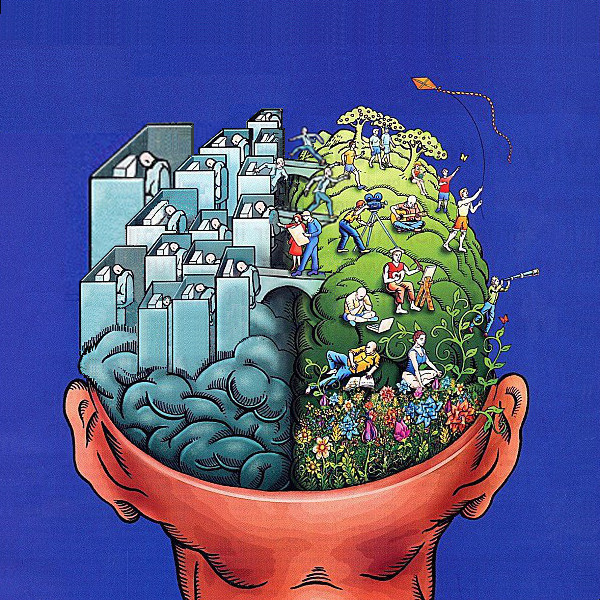

With all this extra knowledge gained, it is possible to further enhance the first illustration that already showed so inventively the partitioning of the two basic functionalities of the brain to this:

|

As a first step, to denote the extra predictive value of using abstractions, the left hemisphere has been lifted slightly, going further upwards to the left (as good a possible).

And the pitfalls are displayed as follows (these are more numerous beacause something has to be learned from of all of this):

- the number of cubicles is made to correspond (approximately) to the number of concepts, getting less going to the left and getting further away from reality.

- the "persons" controlling the concept cubicles have their heads turned away from reality (as before).

- the number of figures crossing over from reality and towards abstractions is made considerably larger than those going from abstractions back towards reality.

The crucial lesson to be learned from this all

is of course this: if reasonings or arguments are intended to lead to

something having sense, then always take care that their outcome says

something about reality. The world outside of the model in your head. This

is the step that breaks the inward spiral that leads to addictions.

The crucial lesson to be learned from this all

is of course this: if reasonings or arguments are intended to lead to

something having sense, then always take care that their outcome says

something about reality. The world outside of the model in your head. This

is the step that breaks the inward spiral that leads to addictions. This sounds really simple, but the number of cases that abide by it relative to those that don't, is extremely low - outside of the world of the natural sciences where this step is encoded (

Go to General semantics list

here

![]() , all

articles here

, all

articles here

![]() , site home here

, site home here

![]() .

.