Bronnen bij Nabije toekomst: zonder mensheid

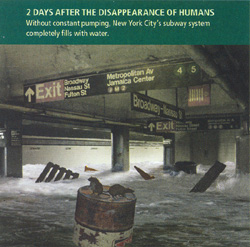

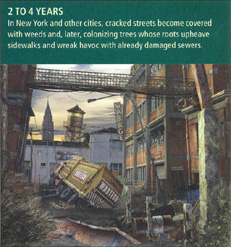

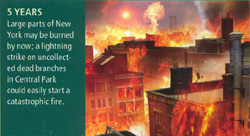

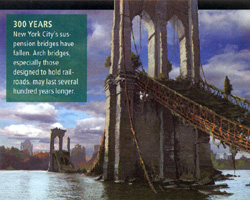

Een toekomst zonder mensheid is geen onbekend begrip in de sciencefiction

van rond de jaren zestig. Maar meer recent kwam er wijder aandacht voor toen

literatuurprofessor Alan Weisman er een boek over schreef genaamd The

World without Us. Naar aanleiding van het verschijnen (juni 2007) heeft

Scientific American (juni 2007) een artikel gewijd aan hetzelfde

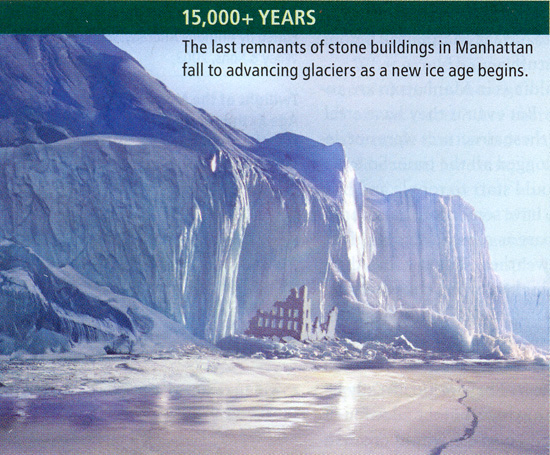

onderwerp. Onderstaand wat illustraties uit dit artikel, als mogelijke visie

op het verval (de middelste vier plaatjes en de tekst in het bovenste kunnen

door erop te klikken vergroot worden).

Tussengevoegd, een bericht 2015, vier jaar na de kernramp

in Fulushima (de Volkskrant, 18-10-2015, door Tonie Mudde. Foto's: Guillaume Bression -

Carlos Ayesta):

En de beelden:

Met als conclusie: die illustraties uit Scientific American

onderschatten vermoedelijk de snelheid waarmee dit proces gaat.

Terug naar de chronologie. Want na het verschijnen van de SciAm-publicatie

kwam er ook ruimer aandacht voor het onderwerp

(de Volkskrant, 06-09-2008, door Wim Wirtz):

En ook de "echte" wetenschap durft zich met de zaak te bemoeien (New Scientist, 4/5/2008, Vol. 197 Issue 2650, p32-35, door Debora

MacKenzie):

| |

Are we doomed?

The very nature of civilisation may make its demise inevitable, says Debora

MacKenzie

DOOMSDAY. The end of civilisation. Literature and film abound with tales of

plague, famine and wars which ravage the planet, leaving a few survivors

scratching out a primitive existence amid the ruins. Every civilisation in

history has collapsed, after all. Why should ours be any different?

Doomsday scenarios typically feature a knockout blow: a

massive asteroid, all-out nuclear war or a catastrophic pandemic. Yet there is

another chilling possibility: what if the very nature of civilisation means that

ours, like all the others, is destined to collapse sooner or later?

A few researchers have been making such claims for years.

Disturbingly, recent insights from fields such as complexity theory suggest that

they are right. It appears that once a society develops beyond a certain level

of complexity it becomes increasingly fragile. Eventually, it reaches a point at

which even a relatively minor disturbance can bring everything crashing down.

Some say we have already reached this point, and that it is

time to start thinking about how we might manage collapse. Others insist it is

not yet too late, and that we can - we must - act now to keep disaster at bay.

History is not on our side. Think of Sumeria, of ancient

Egypt and of the Maya. In his 2005 best-seller, Jared Diamond of the University

of California, Los Angeles, blamed environmental mismanagement for the fall of

the Mayan civilisation and others, and warned that we might be heading the same

way unless we choose to stop destroying our environmental support systems.

Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute in Washington DC

agrees. He has that governments must pay more attention to vital environmental

resources. "It's not about saving the planet. It's about saving civilisation,"

he says.

Others think our problems run deeper. From the moment our

ancestors started to settle down and build cities, we have had to find solutions

to the problems that success brings. "For the past 10,000 years, problem solving

has produced increasing complexity in human societies," says Joseph Tainter, an

archaeologist at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and author of the 1988

book The Collapse of Complex Societies.

If crops fail because rain is patchy, build irrigation

canals. When they silt up, organise dredging crews. When the bigger crop yields

lead to a bigger population, build more canals. When there are too many for ad

hoc repairs, install a management bureaucracy, and tax people to pay for it.

When they complain, invent tax inspectors and a system to record the sums paid.

That much the Sumerians knew.

Diminishing returns

There is, however, a price to be paid. Every extra layer of organisation imposes

a cost in terms of energy, the common currency of all human efforts, from

building canals to educating scribes. And increasing complexity, Tainter

realised, produces diminishing returns. The extra food produced by each extra

hour of labour - or joule of energy invested per farmed hectare - diminishes as

that investment mounts. We see the same thing today in a declining number of

patents per dollar invested in research as that research investment mounts. This

law of diminishing returns appears everywhere, Tainter says.

To keep growing, societies must keep solving problems as they

arise. Yet each problem solved means more complexity. Success generates a larger

population, more kinds of specialists, more resources to manage, more

information to juggle - and, ultimately, less bang for your buck.

Eventually, says Tainter, the point is reached when all the

energy and resources available to a society are required just to maintain its

existing level of complexity. Then when the climate changes or barbarians

invade, overstretched institutions break down and civil order collapses. What

emerges is a less complex society, which is organised on a smaller scale or has

been taken over by another group. ...

Is Tainter right? An analysis of complex systems has led

Yaneer Bar-Yam, head of the New England Complex Systems Institute in Cambridge,

Massachusetts, to the same conclusion that Tainter reached from studying

history. Social organisations become steadily more complex as they are required

to deal both with environmental problems and with challenges from neighbouring

societies that are also becoming more complex, Bar-Yam says. This eventually

leads to a fundamental shift in the way the society is organised.

"To run a hierarchy, managers cannot be less complex than the

system they are managing," Bar-Yam says. As complexity increases, societies add

ever more layers of management but, ultimately in a hierarchy, one individual

has to try and get their head around the whole thing, and this starts to become

impossible. At that point, hierarchies give way to networks in which

decision-making is distributed. We are at this point.

This shift to decentralised networks has led to a widespread

belief that modern society is more resilient than the old hierarchical systems.

"I don't foresee a collapse in society because of increased complexity," says

futurologist and industry consultant Ray Hammond. "Our strength is in our highly

distributed decision making." This, he says, makes modern western societies more

resilient than those like the old Soviet Union, in which decision making was

centralised.

Things are not that simple, says Thomas Homer-Dixon, a

political scientist at the University of Toronto, Canada, and author of the 2006

book The Upside of Down. "Initially, increasing connectedness and diversity

helps: if one village has a crop failure, it can get food from another village

that didn't."

As connections increase, though, networked systems become

increasingly tightly coupled. This means the impacts of failures can propagate:

the more closely those two villages come to depend on each other, the more both

will suffer if either has a problem. "Complexity leads to higher vulnerability

in some ways," says Bar-Yam. "This is not widely understood."

The reason is that as networks become ever tighter, they

start to transmit shocks rather than absorb them. "The intricate networks that

tightly connect us together - and move people, materials, information, money and

energy - amplify and transmit any shock," says Homer-Dixon. "A financial crisis,

a terrorist attack or a disease outbreak has almost instant destabilising

effects, from one side of the world to the other."

For instance, in 2003 large areas of North America and Europe

suffered when apparently insignificant nodes of their respective electricity

grids failed. And this year China suffered a similar blackout after heavy snow

hit power lines. Tightly coupled networks like these create the potential for

propagating failure across many critical industries, says Charles Perrow of Yale

University, a leading authority on industrial accidents and disasters.

Credit crunch

Perrow says interconnectedness in the global production system has now reached

the point where "a breakdown anywhere increasingly means a breakdown

everywhere". This is especially true of the world's financial systems, where the

coupling is very tight. "Now we have a debt crisis with the biggest player, the

US. The consequences could be enormous."

"A networked society behaves like a multicellular organism,"

says Bar-Yam, "random damage is like lopping a chunk off a sheep." Whether or

not the sheep survives depends on which chunk is lost. And while we are pretty

sure which chunks a sheep needs, it isn't clear - it may not even be predictable

- which chunks of our densely networked civilisation are critical, until it's

too late.

"When we do the analysis, almost any part is critical if you

lose enough of it," says Bar-Yam. "Now that we can ask questions of such systems

in more sophisticated ways, we are discovering that they can be very vulnerable.

That means civilisation is very vulnerable."

... Nevertheless, Homer-Dixon thinks we should be taking

action now. "First, we need to encourage distributed and decentralised

production of vital goods like energy and food," he says. "Second, we need to

remember that slack isn't always waste. A manufacturing company with a large

inventory may lose some money on warehousing, but it can keep running even if

its suppliers are temporarily out of action."

The electricity industry in the US has already started

identifying hubs in the grid with no redundancy available and is putting some

back in, Homer-Dixon points out. Governments could encourage other sectors to

follow suit. The trouble is that in a world of fierce competition, private

companies will always increase efficiency unless governments subsidise

inefficiency in the public interest. ...

"This is the fundamental challenge humankind faces. We need

to allow for the healthy breakdown in natural function in our societies in a way

that doesn't produce catastrophic collapse, but instead leads to healthy

renewal," Homer-Dixon says. This is what happens in forests, which are a patchy

mix of old growth and newer areas created by disease or fire. If the ecosystem

in one patch collapses, it is recolonised and renewed by younger forest

elsewhere. We must allow partial breakdown here and there, followed by renewal,

he says, rather than trying so hard to avert breakdown by increasing complexity

that any resulting crisis is actually worse.

Lester Brown thinks we are fast running out of time. "The

world can no longer afford to waste a day. We need a Great Mobilisation, as we

had in wartime," he says. "There has been tremendous progress in just the past

few years. For the first time, I am starting to see how an alternative economy

might emerge. But it's now a race between tipping points - which will come

first, a switch to sustainable technology, or collapse?"

Tainter is not convinced that even new technology will save

civilisation in the long run. "I sometimes think of this as a 'faith-based'

approach to the future," he says. Even a society reinvigorated by cheap new

energy sources will eventually face the problem of diminishing returns once

more. Innovation itself might be subject to diminishing returns, or perhaps

absolute limits.

Studies of the way by Luis Bettencourt of the Los Alamos

National Laboratory, New Mexico, support this idea. His team's work suggests

that an ever-faster rate of innovation is required to keep cities growing and

prevent stagnation or collapse, and in the long run this cannot be sustainable.

The stakes are high. Historically, collapse always led to a

fall in population. "Today's population levels depend on fossil fuels and

industrial agriculture," says Tainter. "Take those away and there would be a

reduction in the Earth's population that is too gruesome to think about."

If industrialised civilisation does fall, the urban masses -

half the world's population - will be most vulnerable. Much of our hard-won

knowledge could be lost, too. "The people with the least to lose are subsistence

farmers," Bar-Yam observes, and for some who survive, conditions might actually

improve. Perhaps the meek really will inherit the Earth. |

Het idee van het opsplitsen van de economie in min

of meer zelfstandig functionerende lokale eenheden is al geformuleerd door de

redactie hier

. .

De kans op het tot stand komen van zoiets is niet groot - zegt

bijvoorbeeld ook de volgende waarnemer, tezamen met het noemen van de

waarschijnlijke grootste horde (de Volkskrant, 02-08-2008):

Er volgde niet veel.

Een nieuwe poging in de publiciteit (de Volkskrant, 23-09-2009, van verslaggever Martijn van Calmthout):

En zeg niet dat er niet allang gewaarschuwd is (de Volkskrant, 09-01-2010, door Martijn van Calmthout):

Een voorbeeldje van dat laatste (de Volkskrant, 02-01-2010, door Leon

de Winter):

En waarom krijgt deze nitwit (op dit vakgebied) deze ruimte in de

krant: omdat hij een bekende schrijver is. ...

Terug naar de meer redelijke mensen (de Volkskrant, 24-09-2011, door Gerard Reijn):

Aanvulling in 2019: dit lijkt tot nu toe allemaal naadloos uit te komen

...

Naar De toekomst

,

of site

home ,

of site

home

·. ·.

|